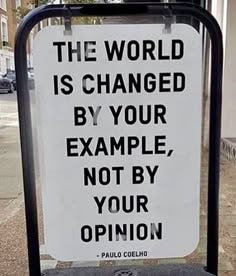

“It had long since come to my attention that people of accomplishment rarely sat back and let things happen to them. They went out and happened to things.”

―Leonardo da Vinci

I never thought I’d find myself questioning the quiet, almost invisible habit so many of us carry: the habit of waiting. Waiting for clarity, for permission, for the right opportunity, the perfect timing, or some long-awaited sign of validation. It’s so deeply ingrained, it hardly feels like a choice.

I’m patient. I’m reflective. I’m wise. These are qualities I’ve built with care, layer by layer, believing they were essential to becoming someone thoughtful and intentional. And they are. But I also believed they were required, that maturity meant holding back, waiting for the right signals before stepping forward. It always seemed harmless, even noble. After all, doesn’t (all) accomplishment require patience? Doesn’t growth take time, alignment? What I never realized is that waiting is, in its own quiet way, a kind of submission. A passive posture. A belief that, eventually, the world will knock gently and offer me a door to walk through.

It’s a quiet thing, really, the moment a person stops waiting.

It didn’t come with a bang. There was no thunder, no epiphany, no slow-motion montage of awakening. The moment I stopped waiting for life to happen to me was, quite honestly, a whisper. A quiet click somewhere inside my chest. A shift in the air that only I could feel. A thought I didn’t even dare say out loud.

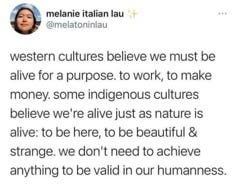

I’m sure many of you who’ve dared to scratch beneath the surface of things have asked this question: How do you “happen to life” in a world designed to keep most people waiting? How do you carve a path forward when the system where success is tangled in privilege, where safety nets cushion some and others are born into sinkholes. My husband and I return to this question often. He says people who “make it” are mostly lucky. That success isn’t some tidy result of talent or hard work, it’s a lottery. He believes that whether someone ends up successful or not has very little to do with personal merit, and everything to do with where they started and what they were handed. And he’s not wrong. Luck is real, and often brutally unfair. Life isn’t a meritocracy; it’s a rigged game disguised as one, full of velvet ropes and invisible shortcuts. That’s the architecture of the world we live in.

And I’ll be the first to admit: I hate it. I hate how quietly privilege moves, how invisible it stays until someone dares to name it. I hate the arrogance of unexamined advantage, the kind that confuses comfort for character. And even when privilege is named, it gets dismissed with alarming speed. People flinch, recoil, or insist the playing field is level if you just work hard enough. But that’s a myth. And it’s one I refuse to pass along as truth.

It doesn’t stop there. When you bring in biology, things get even more complicated. As Robert Sapolsky shows in his work, much of what we believe to be “choice” is, in fact, a cocktail of hormones, early experiences, inherited trauma, and neurochemical wiring. Our decisions are less free will than we’d like to think and more like patterns playing themselves out. We are shaped long before we realize we’re shaping anything.

So yes, this work of becoming, of choosing to show up, to act, to build something from nothing… is unbelievably hard. But despite the mess and unfairness of it all, there remains one wild, inconvenient, beautiful truth I keep returning to: we still have a choice. Not a guarantee. Not a fair shot. But a shot, nonetheless. And yet, that’s exactly why it matters.

The quiet rebellion

To choose, knowing the odds are against you, is not naïve, it’s rebellious. It’s not delusion, it’s creative defiance. It’s the only real agency many of us will ever have: the power to keep showing up, to invent a life inside a system that wasn’t built for us, to stand at the edge of what we were given and say, I will build anyway. Somewhere deep in that process, something shifts. We have the chance (however slim, however rigged) to meet life halfway. To show up and reach for something beyond our immediate conditions. To grab the thread of a thought and pull, even if we don’t know what it’s attached to. To shape our minds around reality instead of letting it crush us into passivity.

“I overcame myself, the sufferer; I carried my own ashes to the mountains; I invented a brighter flame for myself.”

― Nietzsche

But I can’t lie. there are days I feel like I’m carrying ashes. Burned out by the weight of trying, by the sheer exhaustion of resisting both external systems and internal wiring. The work of self-invention is not glamorous. It’s slow. Lonely. Invisible.And most importantly: unrewarded, at least by conventional standards.

Here’s the part nobody really teaches you: the how. That’s the secret sauce. That’s the piece you can’t copy off someone else’s paper. The how is earned, and it’s earned in the doing. The mundane, frustrating, unseen grind. The how is showing up again and again, even when you’re tired, uninspired, and invisible. It’s working when no one is clapping. It’s doing the thing, especially when it’s boring or beneath your talent or wildly inconvenient. You don’t just manifest your dreams from a Pinterest board. You get your hands dirty: making, testing, failing, reimagining. It means returning, again and again, to an idea not because it is flawless, but because it refuses to let go of you. You build things from the bones up: messily, incrementally, by engaging with the world as it is.

I say this not from a place of detached theory, but from lived practice. Balancing multiple jobs, iterating across several projects, constantly mingling ideas and exploring the fragile intersection between creativity and commerce. It is in this continuous loop of action and reflection that one slowly discovers a thread of mastery, a synthesis of art and utility, of personal curiosity and public service. There is, in the end, something noble and deeply human in the ongoing effort to contribute value to a world that does not ask for it, but quietly benefits when we offer it anyway.

And my Buddha, does it take time. I used to think success was about mastering one thing. But now I know it’s about accumulating twenty different things and figuring out how to make them all sit at the same dinner table. It’s about stacking skills like blocks—emotional regulation, storytelling, budgeting, stamina, vision, humility, negotiation, curiosity—and letting them compound over time. Compound interest for character.

And you have to believe in things no one else sees (yet). You have to build in the dark. You have to work for years on something that doesn’t pay off in likes or love or external recognition. You have to keep going without applause. Not being admired. Not being celebrated. Just trusting in the messy, ridiculous, unsexy process of slowly becoming.

It’s about solving one problem at a time. Learning to understand value. Learning to see leverage. Learning how to carry yourself through seasons of doubt without running back to comfort. It’s about choosing to live in the real world, as it is.

In all my years, I’ve maybe met two people who truly happened to life. People who didn’t wait for permission. People who didn’t outsource their becoming. You could feel the tremble beneath their certainty, the quiet hum of someone who had stepped out of the realm of excuses and into full responsibility. They weren’t innocent anymore. They knew that once you choose to show up, you can’t go back to pretending you didn’t know how much power you actually had.

And that’s the most terrifying and most freeing thing of all. Because no one tells you that to really live is to risk unraveling. To act is to disturb the stillness. To “happen to things” means to stand at the edge of your own abyss, knees shaking, heart pounding… and jump anyway!!

And maybe you fail. Maybe you fall. But at least it’s your fall. And falling, in your own name, is still a form of flight.

It’s a quiet thing, really. The moment a person stops waiting.