Cognitive artifacts, high-order thinking and human agency

With AI taking on a substantial share of our “mental load,” it becomes crucial to redefine what it means to “think” in a world where cognitive processes are increasingly shared across human and technological agents.

The concept of *distributed epistemic labor* offers a (somewhat fresh) perspective on this question, viewing cognitive work not as the sole domain of individual minds but as an interconnected network of humans, machines, and tools. Trust in these technological components is vital, as it creates a dynamic that challenges traditional boundaries between human cognition and external aids, potentially overemphasizing reliance while fostering shared agency and co-operation.

Distributed Epistemic Labor: The Foundations of Shared Thinking

Epistemic labor involves all activities related to acquiring, processing, and validating knowledge. Historically, these tasks were managed by individuals or small groups of experts. However, distributed cognition redefines cognition as a collaborative process involving people, tools, and technologies. While this concept expands cognitive potential, it also challenges traditional epistemology by redefining how knowledge is produced and validated. Additionally, it raises ethical questions around accountability, trust, and bias within these distributed systems. What’s particularly intriguing is Edwin Hutchins’ (2000) insight into interaction as a source of novel structure, highlighting how collaboration and interconnected processes can lead to entirely new ways of organizing and understanding knowledge.

The Role of Cognitive Artifacts in Amplifying Humanity

Do cognitive artifacts reduce human agency, or do they free us for higher-order thinking?

Cognitive artifacts — tools or technologies that aid thinking — serve as mental amplifiers, as Don Norman (1993) suggests. These artifacts enhance and organize our cognitive abilities, becoming integral components of an extended system of thought. They don’t replace human cognition; they elevate it.

Take language, for example. Language is not just a medium for communication; it’s a profound cognitive artifact that externalizes thought, enabling us to share and build ideas collectively. Through language, cognition becomes a distributed process, embedded in interactions and shared understandings.

Without language, we might be much more akin to discrete Cartesian ‘inner’ minds, in which high-level cognition relies largely on internal resources. But the advent of language has allowed us to spread this burden into the world. Language, thus construed, is not a mirror of our inner states but a complement to them. (Clark and Chalmers, 1998)

Language is humanity’s most enduring asset. It’s the bridge connecting ideas, people, and generations, from the first cave drawings to today’s sophisticated philosophical debates. In the era of generative AI, large language models (LLMs), and digital storytelling, language reveals its true value — not merely as a tool but as a blueprint for progress and a reflection of human potential.

The Extended Mind and Distributed Cognition

Cognitive artifacts do more than enhance thinking; they transform our understanding of the self. The extended mind hypothesis (Clark & Chalmers, 1998) proposes that cognition is not confined to the brain but distributed across tools, technologies, and social networks. Our “self” extends beyond the biological, integrating both internal resources and external supports.

This has profound implications for agency and accountability. As Clark (2003) notes, the distinctive intelligence of human brains lies in their ability to form deep, complex relationships with non-biological aids.

Human enhancement is not a promising strategy to become smarter yet, individuals might rather rely on the available technologies to improve their performance. As outlined before, individuals do not rely on technical tools all the time, but the distribution of cognitive processes onto internal and external resources rather depends on factors such as tool design, one’s abilities, or metacognitive beliefs (…) What is special about human brains, and what best explains the distinctive features of human intelligence, is precisely their ability to enter into deep and complex relationships with non-biological, props, and aids’’ (Clark, 2003, p.5)

The term ‘extended cognition’ identifies an important and influential body of work within the philosophy of mind ( Clark, 2008). Although the notion of extended cognition is intended to challenge our bio- and neuro-centric intuitions (and prejudices) regarding the material bases of intelligence, there is a sense in which the existing philosophical debate remains skewed towards the biological realm.

Trust in Human-Artifact Systems

In systems where humans and artifacts collaborate, trust becomes the glue binding these elements into cohesive units. Cognitive tasks are distributed between humans and technologies — algorithms, data platforms, or AI systems — with each element relying on the other’s reliability. But this integration raises a critical epistemological question: Can we ‘trust’ artifacts?

Traditional views argue that trust requires intentionality and moral agency, qualities unique to humans. Under this lens, we rely on technology but do not genuinely ‘trust’ it. This distinction matters, especially as artifacts often lack transparency, functioning as “black boxes” whose inner workings are opaque. Onora O’Neill (2020) points out that while digital technologies were once celebrated for fostering open discourse, they now obscure the trustworthiness of information, introducing epistemic opacity.

Some scholars argue that trust can extend to artifacts, not due to their inherent qualities but because of the systems that produce and manage them. Trust, in this sense, becomes less about the artifact itself and more about the accountability and ethical practices of the organizations deploying them. It’s not the algorithm we trust but the assurance that it operates reliably and ethically within established frameworks.

This view reframes trust as a dynamic interaction between performance, transparency, and ethical oversight, demanding new ways to evaluate and engage with cognitive artifacts in increasingly complex systems.

Cognitive artifacts challenge us to rethink agency, cognition, and trust. They don’t diminish human capabilities; they redistribute and amplify them, freeing us for higher-order thinking. But this redistribution introduces ethical and epistemological complexities, especially as technologies grow more opaque and integrated into our cognitive processes. The challenge lies in balancing the immense potential of these tools with the accountability and trust necessary to use them responsibly. As we continue to innovate, the relationship between humans and cognitive artifacts will remain central to shaping a future where technology serves as both a partner and a catalyst for human progress.

Thinking as a Networked Process?

The future of thinking is no longer confined to individual minds; it is distributed across systems that integrate human, digital, and artificial intelligence. Distributed epistemic labor redefines cognition as a networked process, with trust as the essential adhesive that binds these networks together. In this interconnected landscape, thinking becomes a collaborative enterprise shaped by the interplay between human intuition and algorithmic precision. As we continue to delegate cognitive tasks to AI and other technologies, our ability to calibrate and retain cognitive agency will determine whether these tools enhance or erode our capacity for critical thinking and wise action. Trust remains pivotal in extended cognitive systems, enabling effective collaboration between humans and machines and ensuring that technological tools support — rather than hinder — our cognitive autonomy.

________________________

In closing,

I hope this perspective on distributed cognition and epistemic labor in an AI-enhanced world highlights the critical importance of understanding AI’s psychological impacts, educating the public on its risks and benefits, and exploring how individual differences in trust and reliance shape our interactions with these technologies. As user-friendly AI tools increasingly facilitate cognitive offloading, it’s essential that we prioritize responsible design and thoughtful integration to ensure these systems empower, rather than diminish, human potential in the AI-driven future.

[If AI assumes our mental tasks, what remains of human thought? Can we still claim agency in a world where cognition is shared between humans and machines, or must we redefine what it means to truly “think”?]

References:

Clark, A. (2003). Natural-born cyborgs: Minds, technologies and the future of human intelligence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clark, A. (2008). Supersizing the mind: Embodiment, action, and cognitive extension. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Clark, A., & Chalmers, D. (1998). The extended mind. Analysis, 58(1), 7–19.

Hutchins, E. (2000). Distributed cognition. San Diego: IESBS, University of California.

Norman, D. A. (1993). Things that make us smart: Defending human attributes in the age of the machine. Addison-Wesley Longman, MA.

O’Neill, O. (2020). Questioning trust. In The Routledge Handbook of Trust and Philosophy (1st ed., p. 11). Routledge. ISBN 9781315542294.

More:

Grinschgl, S., & Neubauer, A. C. (2022). Supporting cognition with modern technology: Distributed cognition today and in an AI-enhanced future. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 5, 908261. https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2022.908261

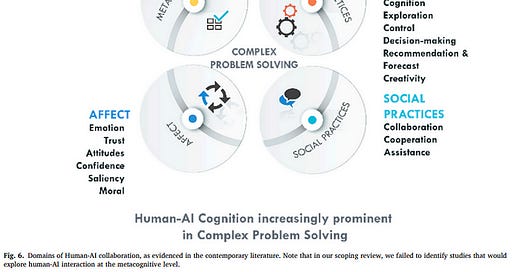

Joksimovic, S., Ifenthaler, D., Marrone, R., De Laat, M., & Siemens, G. (2023). Opportunities of artificial intelligence for supporting complex problem-solving: Findings from a scoping review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 4, 100138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100138

Hollan, J., Hutchins, E., & Kirsh, D. (2000). Distributed cognition: Toward a new foundation for human-computer interaction research. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 7, 174–196. https://doi.org/10.1145/353485.353487

Smart, P. (2017). Situating machine intelligence within the cognitive ecology of the internet. Minds and Machines, 27(2), 357–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-016-9416-z